How the benefit cap harmed mental health and potentially pushed people further away from the labour market

November 26, 2020

The benefit cap is a policy that is popular both with the public and with government. The benefit cap puts a limit on the total amount a family with no-one in full-time employment can receive from the government in social security. The public buy into the intuition laid out by George Osborne when the cap was announced just over 10 years at the Conservative Party conference: “no family should get more from living on benefits than the average family gets from going out to work”. It is popular with government in part because it reduces welfare spending and will continue to do so more for many years because inflation will push more people over threshold for the cap (see Donald Hirsh’s post). But, the benefit cap is also popular with government because there is some evidence it helps some people get back into work.

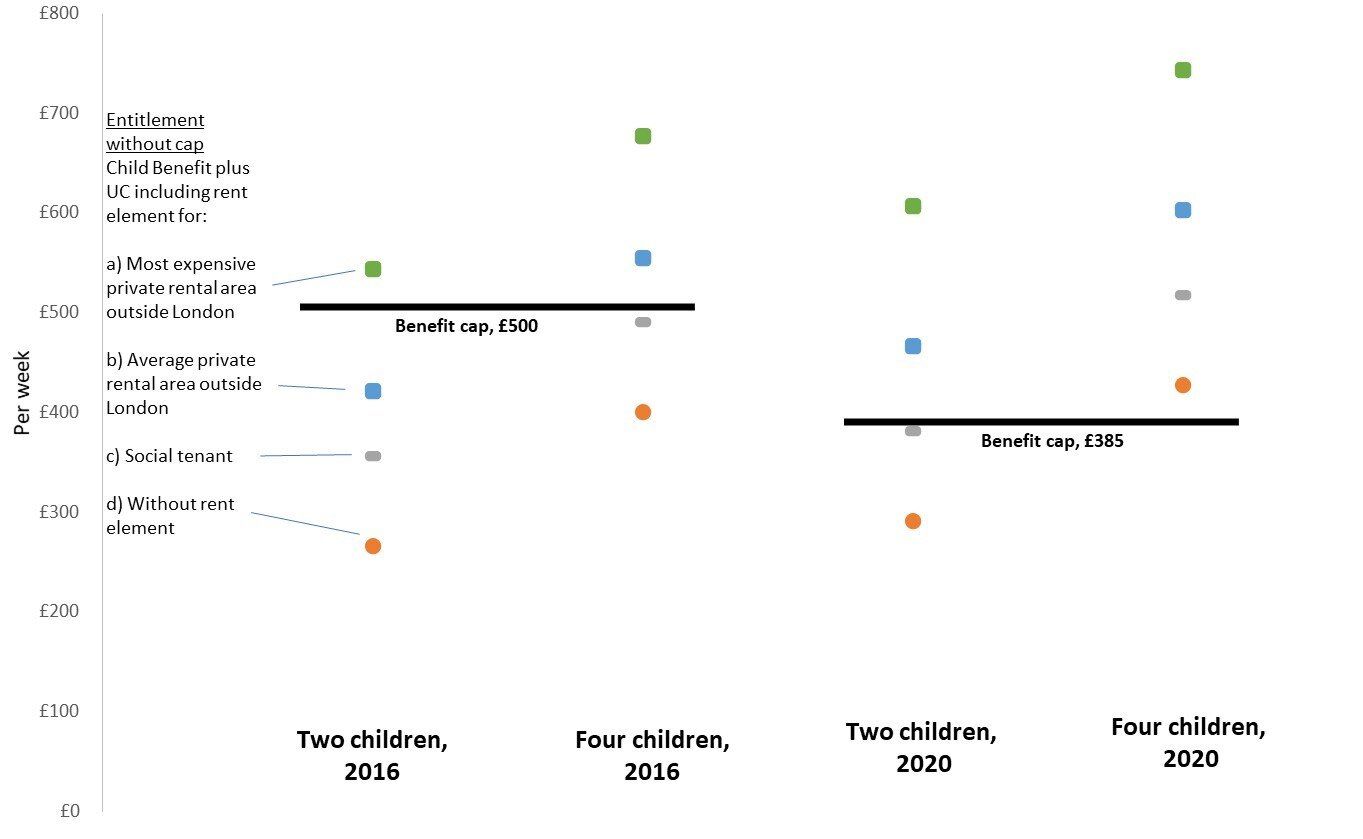

Despite being popular, the benefit cap meaningfully reduced financial support for large (often lone parent) families and those with high housing costs, and broke the link between needs and entitlements in the British social security system. Indeed, one aspect of this debate that has, to date, largely been overlooked is how severing this link between needs and entitlements may impact the mental health of those affected by the benefit cap.

In November 2016 the cap was reduced from £26,000 per year to £23,000 per year for families in London (£15,410 for single people) and to £20,000 (13,400 for single people) outside the capital. We treat this reform as a natural policy experiment, comparing those at-risk of being capped and those who were not. We draw on a survey of around 1.4 million people, some of whom were interviewed before the cap was lowered and some who were interviewed afterwards. We therefore compare the risk of experiencing poor mental health for both those at-risk of being capped and those not at-risk of being capped, before and after the reform.

Our key finding is summarised in this graph.

On the left hand side of the chart we see that people who were not at-risk of being capped experienced a small increase in the probability of reporting mental ill health comparing people interviewed before November 2016 and those interviewed afterward. This is consistent with the general trend in mental health over this period.

On the right-hand side of the chart we see what happened to those at-risk of being capped. For this group we see a quite different pattern: they experienced a far larger rise in the risk of reporting mental ill health after the benefit cap had been lowered in November 2016.

But, these negative mental health effects do not emerge over night. Rather, we find that these negative effects on mental health emerge over a number of months. By the end of our study period, the risk of experiencing mental ill health among those at-risk of being capped had increased by around 10 percentage points, a relative increase of around 50%. To put this into perspective, in November 2019 there were ~76,000 households being capped. Our estimates suggests that at least 16,000 people (~21%) in these households would have been living with depression-like symptoms if the benefit cap had remained unchanged, with around 6,600 additional people (an additional 9%) experiencing depressive-like symptoms as a result of the lowering of the cap.

One implication of this finding is that the benefit cap may simultaneously increase job search activity and even re-employment for some of those affected, while at the same time resulting in a non-trivial number of people experiencing poorer mental health. This is particularly important because many of those experiencing poorer mental health will still be out of work and so the effect of the cap could be to push them even further away from the labour market. Indeed, some of those now in work may exit more quickly because of their health while others may be less likely to get work again in the near future.

The benefit cap reminds us of the unintended consequences of policy and illustrates how they can exacerbate inequalities. The cap not only increases the risk of mental ill health but it does so among lone parents (usually women) who live in high-rent areas. In this respect, our results reinforce other work which shows how lone parents have been particularly badly hit by recent welfare reforms and subsequent economic hardship, for example being disproportionately likely to be sanctioned (have their welfare payments temporarily stopped) and to be evicted. One of the troubling aspects of many of the recent reforms to social security is how often these changes seem to penalise lone parents and their children. In this instance, our analysis suggests attempts to promote labour market activation and to reduce costs through the benefit cap have had the adverse consequence of damaging the mental health of those exposed to this reform.